My LDC Benefits

Kidney stones

Learn about the symptoms, risks, causes and treatment of this often intensely painful condition.

Overview

Kidney stones are hard objects made of minerals and salts in urine. They form inside the kidneys. You may hear healthcare professionals refer to kidney stones as renal calculi, nephrolithiasis or urolithiasis.

Kidney stones have various causes. These include diet, extra body weight, some health conditions, and some supplements and medicines. Kidney stones can affect any of the organs that make urine or remove it from the body — from the kidneys to the bladder. Often, stones form when the urine has less water in it. This lets minerals form crystals and stick together.

Passing kidney stones can be quite painful. But prompt treatment usually helps prevent any lasting damage. Sometimes, the only treatment needed to pass a kidney stone is taking pain medicine and drinking lots of water. Other times, surgery or other treatments may be needed. It depends on size, location and the type of stone you have.

If you've had more than one kidney stone, your healthcare professional can show you ways to prevent more. This may involve making diet changes, taking medicine or both.

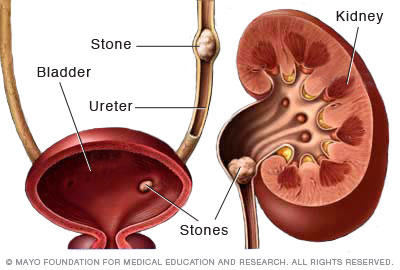

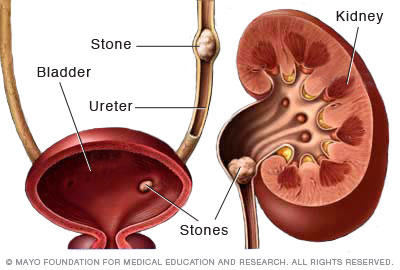

Kidney stones

Kidney stones form in the kidneys. Symptoms may start as stones move into the ureters. The ureters are thin tubes that let urine pass from the kidneys to the bladder. Symptoms of kidney stones can include serious pain, upset stomach, vomiting, fever, chills and blood in the urine.

A kidney stone usually doesn't cause symptoms until it moves around within the kidney or passes into one of the ureters. The ureters are the tubes that connect the kidneys and bladder.

If a kidney stone gets stuck in one of the ureters, it may block the flow of urine and cause the kidney to swell and the ureter to spasm. That can be very painful. At that point, you may have these symptoms:

- Serious, sharp pain in the side and back, below the ribs.

- Pain that spreads to the lower stomach area and groin.

- Pain that comes in waves and varies in how intense it feels.

- Pain or a burning feeling while urinating.

Other symptoms may include:

- Pink, red or brown urine.

- Cloudy or foul-smelling urine.

- A constant need to urinate, urinating more often than usual or urinating in small amounts.

- Upset stomach and vomiting.

- Fever and chills if an infection is present.

Pain caused by a kidney stone may change as the stone moves through your urinary tract. For instance, the pain may shift to a different part of the body or become more intense.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your healthcare professional if you have any symptoms that worry you.

Get a healthcare checkup right away if you have:

- Pain so bad that you can't sit still or find a comfortable position.

- Pain along with upset stomach and vomiting.

- Pain along with fever and chills.

- Blood in your urine.

- Trouble passing urine.

Kidney stones often have no definite, single cause. But many factors may raise your risk.

Kidney stones develop when the urine contains more crystal-forming substances than the fluid in the urine can dilute. These substances include calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate and uric acid. At the same time, the urine may lack substances that prevent crystals from sticking together. That creates an ideal setting for kidney stones to form.

Types of kidney stones

Knowing the type of kidney stone you have helps your healthcare professional figure out its cause and the right treatment for you. This information also can give clues on how to prevent more kidney stones. If you can, try to save your kidney stone if you pass one. Then bring it to your healthcare professional, who can check on what type of kidney stone it is.

Types of kidney stones include:

-

Calcium stones. Most kidney stones are calcium stones. They're usually made of the chemical compound calcium oxalate. Oxalate is a substance made daily by the liver or absorbed from diet. Some fruits and vegetables, as well as nuts and chocolate, have high amounts of oxalate.

Dietary factors, high doses of vitamin D, intestinal bypass surgery and many conditions that affect metabolism can make calcium or oxalate more concentrated in urine.

Calcium stones also can be made of calcium phosphate. This type of stone is more common in metabolic conditions such as renal tubular acidosis. It also may be linked with some medicines for migraines or seizures such as topiramate (Topamax, Trokendi XR, others).

- Uric acid stones. Uric acid stones can form in people who lose too much fluid because of ongoing diarrhea or people who have trouble absorbing nutrients from food; those who eat a high-protein diet or lots of organ meats or shellfish; and those with diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome. Some genetic factors also may raise the risk of uric acid stones.

- Struvite stones. Struvite stones form in response to a urinary tract infection. These stones can grow quickly and become quite large, sometimes with few symptoms or little warning.

- Cystine stones. These stones form in people with a rare genetic condition called cystinuria that causes the kidneys to leak too much of a protein building block called cystine.

Factors that raise your risk of kidney stones include:

- Family or personal history. If someone in your family has had kidney stones, you're more likely to develop stones too. If you've already had one or more kidney stones, you're at higher risk of getting another.

- Dehydration. Not drinking enough water each day can raise your risk of kidney stones. People who live in warm, dry climates and those who sweat a lot may be at higher risk than others.

- Some diets. Eating a diet that's high in oxalate, protein, sodium and sugar may raise your risk of some types of kidney stones. This is especially true with a high-sodium diet. Too much sodium raises the amount of calcium the kidneys must filter. And that greatly raises the risk of kidney stones.

- Obesity. This complex disease involves having too much body fat, and it's been linked with a higher risk of kidney stones.

- Digestive diseases and surgery. Gastric bypass surgery, inflammatory bowel disease or ongoing diarrhea can cause changes in the digestive process. These changes affect how the body absorbs calcium and water. That in turn increases the amounts of stone-forming substances in the urine.

- Other health conditions such as renal tubular acidosis, cystinuria, hyperparathyroidism and repeated urinary tract infections also can raise the risk of kidney stones. A rare genetic condition called primary hyperoxaluria raises the risk of calcium oxalate stones.

- Some supplements and medicines. These include vitamin C, dietary supplements, overuse of laxatives, calcium-based antacids, and some medicines for migraines or depression.

Prevention of kidney stones may include a mix of lifestyle changes and medicines.

Lifestyle changes

You may lower your risk of kidney stones if you:

-

Drink water throughout the day. This is the most important lifestyle change you can make. If you've had kidney stones before, your healthcare professional may tell you to drink enough fluids to pass about 2.1 quarts (2 liters) of urine a day or more. You may be asked to measure how much urine you pass to make sure that you're drinking enough water.

If you live in a hot, dry climate or you exercise often, you may need to drink even more water to produce enough urine. If your urine is light and clear, you're likely drinking enough water.

- Eat fewer oxalate-rich foods. If you tend to form calcium oxalate stones, your healthcare professional may recommend limiting foods rich in oxalates. These include rhubarb, beets, okra, spinach, Swiss chard, sweet potatoes, nuts, tea, chocolate, black pepper, sesame or tahini products, and soy products. Reviewing your diet with a dietitian with expertise in kidney stones is usually helpful.

- Choose a diet low in sodium and animal protein. Lower the amount of sodium you eat. And choose protein sources that don't come from meat or fish, such as legumes. Think about using a salt substitute to flavor foods.

-

Keep eating calcium-rich foods, but use caution with calcium supplements. Calcium in food doesn't have an effect on your risk of kidney stones. Keep eating calcium-rich foods unless your healthcare professional recommends otherwise.

Ask your healthcare professional before taking calcium supplements. These have been linked with a higher risk of kidney stones. You may lower the risk by taking supplements with meals. Diets low in calcium can make kidney stones more likely to form in some people.

Ask your healthcare professional to refer you to a dietitian. The dietitian can help you make an eating plan that lowers your risk of kidney stones.

Medications

Medicines can control the amount of minerals and salts in the urine. They may be helpful in people who form certain kinds of stones. The type of medicine that your healthcare professional prescribes depends on the kind of kidney stones you have. Here are some examples:

- Calcium stones. To help prevent calcium stones from forming, your healthcare professional may prescribe a thiazide diuretic or potassium citrate. If you have calcium oxalate stones due to the rare genetic condition primary hyperoxaluria, you may need other treatments to lower the amount of oxalate in your blood. Your healthcare professional may recommend that you take vitamin B6, also called pyridoxine. Or you may need prescription medicines such as lumasiran (Oxlumo) or nedosiran (Rivfloza).

- Uric acid stones. Your healthcare professional may prescribe allopurinol (Zyloprim, Aloprim, others) to lower uric acid levels in your blood and urine. You also may be prescribed potassium citrate. Sometimes, these medicines may dissolve existing uric acid stones.

- Struvite stones. To prevent struvite stones, your healthcare professional may recommend ways to keep your urine free of bacteria that cause infection. For instance, you may be told to urinate more often and to drink fluids to keep your urine flow good. Rarely, long-term use of antibiotics in small or occasional doses may help achieve this goal. For instance, your healthcare professional may suggest that you take an antibiotic before and for a while after surgery to treat your kidney stones. Medicines called acetohydroxamic acid also may help prevent struvite stones.

- Cystine stones. A diet that's lower in sodium and protein may help prevent cystine stones. Your healthcare professional also may recommend that you drink more fluids so that you urinate more. If those changes alone don't help, medicines called thiol drugs or other newer medicines also may be prescribed. They might make crystals less likely to form.

Diagnosis involves the steps that your healthcare professional takes to find out if you have kidney stones. Diagnosis also can include testing to find the cause and chemical makeup of kidney stones. Your healthcare professional starts by giving you a physical exam. You also may need tests such as:

- Blood tests. Blood tests may reveal too much calcium or uric acid in your blood. Blood test results help track the health of your kidneys. These results also may lead your healthcare professional to check for other health conditions.

- Urine testing. Your healthcare professional may ask you to collect samples of your urine over 24 hours. The 24-hour urine collection test may show that your body is releasing too many stone-forming minerals or too few substances that prevent stones. Follow your healthcare professional's instructions closely. Collecting the urine appropriately is key to make changes in your treatment plan to prevent new stones from forming.

-

Imaging. Imaging tests such as CT scans may show kidney stones in your urinary tract. An advanced scan known as a high-speed or dual energy CT scan may help find tiny uric acid stones. Simple X-rays of the stomach area, also called the abdomen, are used less often. That's because this kind of imaging test can miss small kidney stones.

Ultrasound is another imaging option to diagnose kidney stones.

- Analysis of passed stones. You may be asked to urinate through a strainer to catch any stones that you pass. Then a lab checks the chemical makeup of your kidney stones. Your healthcare professional uses this information to find out what's causing your kidney stones and to form a plan to prevent more kidney stones.

- Genetic testing. Some rare conditions that pass from parent to child make kidney stones more likely. For instance, having cystinuria raises the risk of cystine stones. Primary hyperoxaluria raises the risk of calcium oxalate stones. If your healthcare professional thinks you might have such a condition, your healthcare professional may recommend genetic testing to find out for sure.

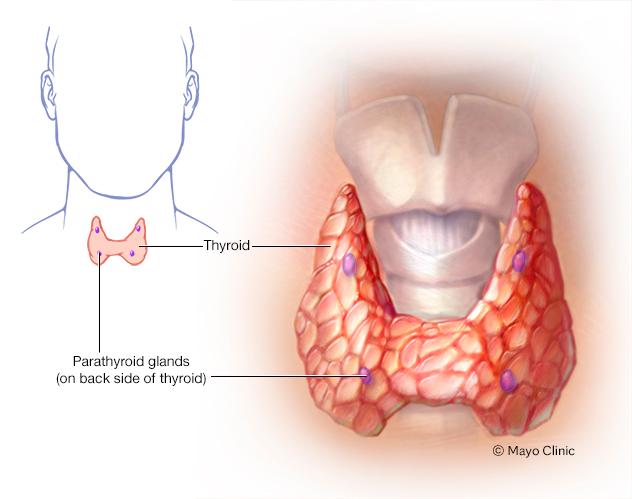

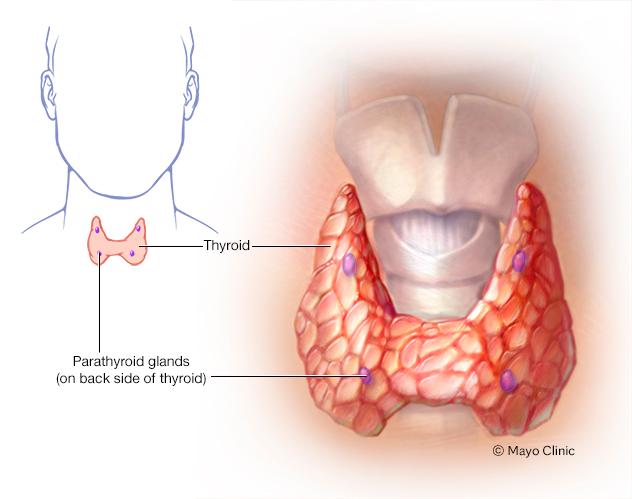

Parathyroid glands

The four tiny parathyroid glands, which lie near the thyroid, make the parathyroid hormone. The hormone plays a role in controlling levels of the minerals calcium and phosphorus in the body.

Treatment for kidney stones varies. It depends on the type of stone and the cause.

Small stones with few symptoms

Most small kidney stones don't require invasive treatment such as surgery. You may be able to pass a small stone by:

- Drinking water. Drinking as much as 2 to 3 quarts (1.8 to 3.6 liters) a day likely will keep your urine dilute and may prevent stones from forming. Unless your healthcare professional tells you otherwise, drink enough fluid. It's ideal to mainly drink water to produce clear or nearly clear urine.

- Pain relievers. Passing a small stone can cause mild to serious discomfort. To relieve mild pain, your healthcare professional may recommend pain relievers such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve). For serious pain, other treatments in the emergency room may be needed.

- Other medicines. Your healthcare professional may give you a medicine to help pass your kidney stone. This type of medicine is known as an alpha blocker. It relaxes the muscles in your ureter. This helps you pass the kidney stone more quickly and with less pain. Examples of alpha blockers include tamsulosin (Flomax) and the drug combination dutasteride and tamsulosin (Jalyn).

Large stones and those that cause symptoms

Kidney stones that are too large to pass on their own may need more-extensive treatment. So might stones that cause bleeding, kidney damage or ongoing urinary tract infections. Treatments may include:

-

Using sound waves to break up stones. For some kidney stones, your healthcare professional may recommend a treatment called extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. This also is known as ESWL. But it depends on the size and location of your stones.

ESWL uses sound waves to create strong vibrations called shock waves that break the stones into tiny pieces that can be passed in urine. The treatment lasts about 45 to 60 minutes. It can cause moderate pain, so you may be given medicines to prevent pain or help relax you.

ESWL can cause blood in the urine and bruising on the back or stomach area. It also can cause bleeding around the kidney and around other nearby organs. It can cause discomfort as the stone fragments pass through the urinary tract too.

-

Surgery to remove very large stones in the kidney. A surgery called percutaneous nephrolithotomy (nef-row-lih-THOT-uh-me) involves removing a kidney stone using small telescopes and tools inserted through a small cut in the back or side.

You receive medicine called a general anesthetic that prevents pain and puts you in a sleep-like state during the surgery. You'll likely recover in the hospital for 1 to 3 days afterward. Your healthcare professional may recommend this surgery if ESWL doesn't help you enough.

-

Using a scope to remove stones. To remove a smaller stone in your ureter or kidney, your surgeon may use a thin lighted tube called a ureteroscope. This instrument is equipped with a camera. The surgeon places the uteroscope through the urethra and bladder to the ureter.

Once the stone is found, special tools can snare the stone or break it into pieces that will pass in the urine. Then the surgeon may place a small tube called a stent in the ureter to relieve swelling and support healing. You may need general or local anesthesia during this procedure.

-

Parathyroid gland surgery. Some calcium phosphate stones are caused by overactive parathyroid glands. These glands are located on the four corners of the thyroid gland, just below the Adam's apple. When these glands make too much parathyroid hormone, that's a condition known as hyperparathyroidism. The condition can cause calcium levels to become too high, and kidney stones may form as a result.

Hyperparathyroidism sometimes happens when a small tumor that isn't cancer forms in one of the parathyroid glands. Or hyperparathyroidism can happen if you develop another condition that leads these glands to make more parathyroid hormone. Removing the tumor from the gland stops kidney stones from forming. Or your healthcare professional may recommend treatment of the condition that's causing your parathyroid gland to make too much of the hormone.

Small kidney stones that don't block your kidney or cause other health troubles can be treated by your primary healthcare professional. But if you have a large kidney stone and have serious pain or kidney troubles, you may need to see a specialist. Your healthcare professional may refer you to a doctor called a urologist or a nephrologist who treats conditions of the urinary tract.

What you can do

To prepare for your appointment:

- Ask if there's anything you need to do before your appointment, such as limit your diet.

- Write down your symptoms, including any that don't seem related to kidney stones.

- Keep track of how much you drink and urinate during a 24-hour period.

- Make a list of all medicines, vitamins or other supplements that you take.

- Take a family member or friend along, if possible, to help you remember what you discuss with your healthcare professional.

- Write down questions to ask your healthcare professional.

For kidney stones, some basic questions include:

- Do I have a kidney stone? If so, what size and type of stone is it, and where in my urinary tract is it?

- Will I need medicine to treat my condition?

- Will I need surgery or another procedure?

- What's the chance that I'll develop another kidney stone? How can I prevent kidney stones in the future?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Should I see a specialist? If so, does insurance typically cover the services of a specialist?

- Do you have any educational material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

Feel free to ask any other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your healthcare professional is likely to ask you questions such as:

- When did your symptoms start?

- Have your symptoms been constant or do they happen once in a while?

- How bad are your symptoms?

- What, if anything, seems to make your symptoms better?

- What, if anything, appears to make your symptoms worse?

- Has anyone else in your family had kidney stones?

© 1998-2025 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research (MFMER). All rights reserved.